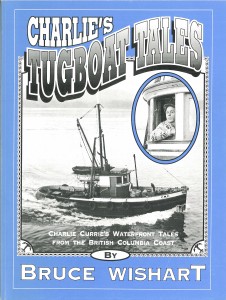

Charlie’s Tugboat Tales is long out of print. The late Captain Charlie Currie was a waterfront icon of the Northwest Coast.

Captain Currie and his wife, “Tugboat Winnie,†ran the 44-foot wooden tug C.R.C., built to Captain Currie’s design at the Prince Rupert Drydock in 1929. They helped people. They helped boats in trouble, hauled supplies into isolated communities when other boats couldn’t get in, and carried barge-loads of school kids on beach picnics.

I am as proud of Tugboat Tales as I am of any other story I’ve ever told. I still sometimes see a battered copy aboard the working boats of the northern fleet, and there is no higher praise than that.

I visited Captain Currie in his museum-like home, recorded his stories, and then gradually built up what I considered to be the definitive version of each tale. They were then blended together to be as much like his voice as possible. Then Charlie read it, and made any changes he wished. The stories ran as a newspaper column, and they were collected as a book in 1997.

For several years after Captain Currie’s death we carried on his weekly chowder gatherings at Sabre Marine, and recovered and restored the C.R.C. Much of what I know about the northern waterfront was learned over chowder and fresh buns around the table in the floating office of Sabre Marine.

Here is my favourite Tugboat Tale. Or rather, it is the one which most frequently finds its way back into my thoughts. It was during the Second World War, when Prince Rupert played a vital role in defending the Canadian coast. Canadian and US troops filled the town, artillery forts guarded the harbour, and North America’s only armoured train ran on the coastal stretch of the railway. The Fisheries patrol vessel CGS Howay was stationed here; and, as Captain Currie described, the Cougar was a private yacht that had been requisitioned for coastal defence.

I can’t escape the image of this poor woman alone as the camp froze to the mud, flooded with incoming tide, and then jarred loose, over and over again for eleven weeks. And it says much about Captain Currie’s nature that he felt so terrible about the two little dogs.

Eleven weeks alone with the ice

It must have been ’42. That was a cold winter. There was a fellow named Arman Auriol logging up at Khutzeymateen Inlet. He’d left his wife in there and gone to town to get more supplies for the winter after we’d towed the camp down there and tied it up. He was going back, but it was froze in so he couldn’t get back to her.

See, there’s the narrows at Khutzeymateen, and a lot of fresh water comes out of there. It hadn’t frozen there for years, but that’s the year it froze.

There was a big slide on the opposite side. Auriol climbed up there quite often in the daytime to see if he could see smoke, but he could never see smoke. He figured she was dead. She figured he got drowned.

There were quite a few boats come along and try to break in. One boat did a lot of damage. She was crazy to try. She was empty, running around following the herring fleet, and the gumwood was above the waterline so that she was cutting the planks.

McAfee at Georgetown financed Auriol, and he wondered why he hadn’t heard from him for awhile. In March he said, “Would you take a run up?†So I run up from Georgetown.

Well, he was there with his boat all right, but he couldn’t get in there. He had no gumwood on his boat at all.

So he came with me and we broke the ice for a couple of days there. There must have been a quarter-mile of it when we started. Then it got so thick, toward the shore, with wet snow frozen too, that I was afraid we were cutting the hull.

So we had to quit. I told Auriol I’d go to town and get a steel boat and come back.

The Navy didn’t think much of the idea. I thought I could get the Howay, but they wouldn’t let me have her. She was only running on one engine because they had the shaft out. All I could get was a yacht some movie actor had down south, the Cougar, I think. A great big clumsy thing, though she had lots of power; she had two 375 Wintons in her. She was anchored in Metlakatla Pass quite a bit; during the war the Navy used to have boats at the first buoy you turn at, at the village there, and each boat coming in had to stop and report. I think the reason they used her there was she wasn’t no good for anything else.

The man at the Navy office says, “You know, she’s not much good. Her sides are like a hungry horse.†You could see all the ribs in her.

Well, they only nosed into the ice a little bit and the engineer come up and says, “We can’t do this, it’s heating up the engine.â€

That was all baloney. He just wanted to get back to town.

But anyway, it was lucky I took a flat-bottomed skiff along aboard the boat. We put it in, and me and Auriol went ashore.

Well, his wife was there. She’d spent eleven weeks alone in the shack there. She had a bad time of it, too, making do with what she had. The camp was dry at low tide, sitting on the mud. It froze there, and then the tide would come in. The tide just kept getting closer and closer. Finally she piled all her food that she had left on the table, and when the float let go it shook everything loose on the floor and everything. She had a hell of a time. Worst of all she had two little dogs with her that would get outside, and the wolves were right there trying to get them.

Anyway, we were crazy taking that skiff in. We should have took another guy. See, because I couldn’t get the skiff back to the boat without another guy with me to drag it on the ice. So we had to take him back again. It was quite awhile after that before the ice let go and come out.

She had a hell of a time. Imagine, that woman alone there for eleven weeks.

Windigo!

I’ve always had a soft spot for westerns, and during the late 1980s I went through a phase of writing western stories—primarily for the magazines of the now-defunct Western Publications in Stillwater, Oklahoma. While researching a major series for True West called “Grandmother’s Land: Sitting Bull in Canada,†I stumbled into this, ah, tasty little story somewhere in the Mounted Police reports.

When the story ran in the quarterly Old West, I accompanied it with an image from the collection of the Glenbow Museum. It showed Swift Runner with a scowling Mountie in pillbox hat. I’ve always found this photo of Swift Runner unsettling.

Approaching it in the nature of protagonist Alan Grant in The Daughter of Time, by Josephine Tey—disregarding the massive shackles, and the knowledge of his horrific crime, and assuming innocence—I think I might have drawn an alarming conclusion. He had a pleasant face, making me think that he was someone who loved to laugh. I would likely have passed a pleasant moment chatting, had I run into him on the street.

Windigo!

First published in OLD WEST, Summer 1990

During the winter, a Windigo ate Swift Runner’s family. Swift Runner was a Cree hunter and trapper from the country north of Fort Edmonton. He was a big man, over six feet tall, and well liked. He was mild and trustworthy, a considerate husband, and very fond of his children (a little too fond of his children, as events proved). All of these traits endeared him to his people and to the traders of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

But this was not enough to allay suspicion when he returned from his winter camp in the spring of 1879 without his wife and family. When he could not give a satisfactory account of their whereabouts, his in-laws became worried. They decided to tell the North West Mounted Police, who had then been in the West for just five years.

Inspector Sévère Gagnon was given the task of investigating Swift Runner’s behavior. He and a small party of policemen accordingly trekked out to the trapper’s camp.

Swift Runner obligingly showed the Mounted Policemen a small grave near his camp. He explained that one of his boys had died and was buried there. Gagnon and his detachment opened the grave and found the bones undisturbed.

That, however, did not explain the human bones scattered around the encampment. Gagnon produced a skull, which Swift Runner willingly told him was that of his wife. Without much prodding, Swift Runner revealed what had happened to the rest of his family.

At first, Swift Runner became haunted by dreams. A Windigo spirit called on him to consume the people around him. The spirit crept through his mind, gradually taking control. Finally he was Windigo, and Swift Runner no longer. Then the Windigo killed and ate Swift Runner’s wife.

This accomplished, the Windigo forced one of Swift Runner’s boys to kill and butcher his younger brother. While enjoying this grisly repast, the spirit hung Swift Runner’s infant by the neck from a lodge pole and tugged at the baby’s dangling feet. It was later shown that he had also done away with Swift Runner’s brother—and his mother-in-law, though he acknowledged that she had been “a bit tough.â€

The revolted Mounted Police party hauled Swift Runner and the mutilated evidence back to Fort Saskatchewan. The trial began on August 8, 1879. The judge and jury did not view the Windigo idea in the same light as the Cree. They saw Swift Runner as a murderer, and the trapper made no attempt to hide his guilt. Stipendiary Magistrate Richardson quickly sentenced him to be hanged.

The sentence presented a problem: the police had never before conducted an execution. Although the Hudson’s Bay Company had once hanged an employee for murder, this was, for all intents and purposes, the first formal execution in western Canada. Staff Sergeant Fred Bagley, a force bugler, was put in charge of the arrangements.

A gallows was erected within the fort enclosure at Fort Saskatchewan, and an old army pensioner named Rogers was made hangman. On the appointed morning, a bitterly cold December 20, Swift Runner was led to the scaffold.

Standing over the trap, the unrepentant cannibal was given the opportunity to address the large crowd that had gathered. He openly acknowledged his guilt, and thanked his jailers for their kindness—then berated his guard for making him wait in the cold!

Nevertheless, the Mounted Police must have accomplished their first execution well enough. A more experienced spectator, a California “forty-niner†named Jim Reade, commented, “That’s the purtiest hangin’ I ever seen, and it’s the twenty-ninth!â€

Nowadays we view as psychosis what the Cree thought to be the work of a Windigo spirit. At one time, in the belt of parkland that borders the northern plains, it was far from being a rare phenomenon. Usually the symptoms were the same as those displayed by Swift Runner. And in one way or another, most of the afflicted Windigos met similar, violent deaths.