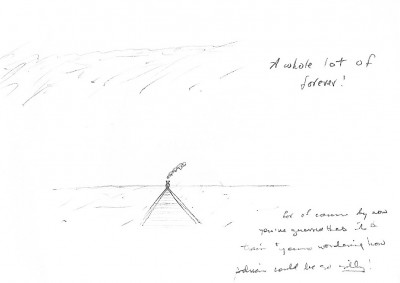

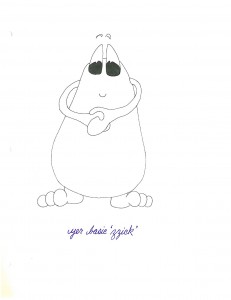

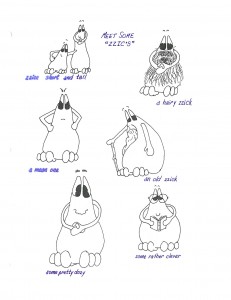

Here’s a little vignette of coastal living, an encounter with a fellow who was sailing solo around the world, that was part of my ongoing conversation with readers of This Week. The “chowder†was a weekly gathering of waterfront veterans, launched in the early 1980s by Captain Charlie Currie. After his death in 1997 we carried it on for another seven or eight years. The chowder was exactly the sort of thing that Eric had gone out into the world hoping to find.

Just words passing between travellers

First published in This Week, September 20, 1998

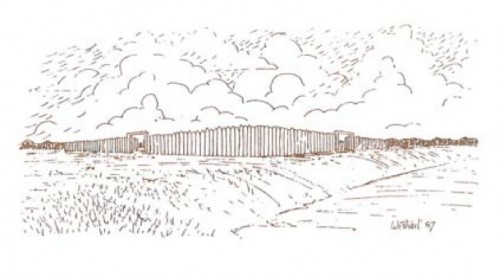

Eric left here Monday night. The Yarra, under tow, rode in the wake of the Exporter and the Sabre. Sunlight evaporated behind the hills across the harbour.

“The colours are softer now,†Lonnie said, “more pastel. That’s a winter sunset.â€

The couple standing beside us were from California. “How’s your film speed?†the woman said. “Would you like to use our tripod?â€

“It’s 200 ASA,†I said. “I can push it.†I was really just watching the magnified boats through the viewfinder.

I wasn’t really in the mood to talk to them because I was thinking about Eric finally leaving. I only came to really know him in the past few months. We talked often about the sea, because he was one of the very few people I’ve met in my wandering from waterfront to waterfront who has read so widely about the sea. His English was much better now. It was well past the stage when an anonymous, but playful, towboater informed me, in an aside, that the only way to learn the language was to begin with profanity and work your way out.

I thought how fitting it was that Eric was slipping out of the harbour in the company of Sabre Marine, because he had become part of Sabre, and how fitting it was that he was going out on the sunset. His sails were furled, the wind was calm, and his friends were taking him to the north wind.

He wasn’t using the Inside Passage. He told me last week that he was worried about delaying too long in getting out into the open Pacific, because he would use up his fresh food too quickly. I thought he should go south to avoid Hecate Strait, but he wasn’t worried. He had been to Cape Horn.

Lonnie waved with her arms reached high, but I could see no evidence through the viewfinder that anyone on the boats had seen her.

If we had known that Eric was leaving today we would have gone to say goodbye again. But he’d been leaving, it seemed, for weeks, and we didn’t know that today would be the day the wind would finally tell him to go. When that damned southeasterly ended.

Lonnie talked to the couple from California. I let my camera down, for the three boats had merged into one as they passed Ocean Dock and slipped toward the harbour mouth. The man was talking about the waterfront park.

I asked if they were coming from Alaska. No, they came in on The Skeena, and were leaving by the ferry on their way to Alaska. Because I was still thinking about Eric I said that they were coming at the right time of the year, and they could see Alaska without too many tourists.

We left them, walking down the uneven boardwalk toward the water taxi, and talked about Eric. He has four years now on that little boat. From Switzerland he went down the Atlantic, a computer hardware builder who was tired of people and tired of how the world had become. He avoided places where tourists came, sought out places where he could discover pockets of unspoiled life. Places where living was slow. He must have liked it here, because after he had appeared suddenly from a winter cruise off Alaska, saying that winter was the only time one could still see the real Alaska, he stayed for months in Prince Rupert.

I have forgotten how many weeks he came up from the Yarra to join us for chowder each Friday. This Week did a story about him on February 1, and I see from it that he arrived here on November 14, 1997, so it must have been around then. He was friendly, but slow to know. Just the sort of person you would think would throw away his working life and set out ‘round the globe with only his luck, his skill, and a little sailboat.

He’s on his way to New Zealand now, with no landfalls and in as straight a line as wind and current will allow. Perhaps we will never see him again, and perhaps we will. The way that new friends and old friends come together almost makes you think that we’re all moving like the tide.

I asked Eric if he would come back to Prince Rupert. He shrugged, and said “maybe,†maybe in three, four years. I told him to stop by for chowder, and he said that he would.

Ken came home from war

First published in This Week, November 10, 1996.

I know a man, the father of a friend. I grew up knowing this man, but over many years my memory may have become distorted. I may get the story a little wrong, but its essence remains the same.

Ken came from the southern tip of Lake Manitoba, where little farms are tucked among hills, marsh and scraggly trees. He was a farm boy. Maybe he dreamed of far-away places, when he was a boy learning the three “Rs†in one of those little one-room schoolhouses with the Union Jack flying out front. Maybe he dreamed of sailing ships and flying aeroplanes. I don’t know. I’ve always guessed that he dreamed of being a good farmer, and nothing more or less.

In September, 1939, the world changed. This is not a fiction created by later historians. The world changed. The British Empire, the foundation of everything Ken learned as a prairie boy, was in very real danger—not of losing its global supremacy, but of actually being overrun. Bombs showered London just a few short months after the invasion of Poland.

Ken joined England’s Royal Air Force. If my memory is correct, his brother joined, too, and his cousin flew in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

These three Connell boys all flew in the big bombers. Ken flew in a Lancaster during the Nuremburg raid. He flew, I think, two tours of duty.

And then Ken came home from the war. He came home with a wife, Pat, who came from Prince Edward Island. Ken and Pat farmed, and then Ken became the manager of a grain elevator; he managed the POOL elevator in Minnedosa and gave me one of my first jobs. He was, and is, prominent in the United Church and the Royal Canadian Legion. He and Pat have done very much, in their quiet way, for the community of Minnedosa since moving there over 20 years ago.

They raised four children, three boys and a girl, all of whom have become fine adults. As Ken and Pat approached retirement they traveled more. They visited their son Kim, an RCMP officer in northern Alberta. They visited their old post-war stomping grounds in the Swan River Valley. Ken and Pat went on Ken’s first visit to England since the end of the Second World War. Ken took up woodworking, and built a basement workshop.

And now Ken and Pat are retired. From memory Ken builds models of the horse-drawn wagons and buckboards that carried the farm families of his youth. He and Pat remain committed to their community, and are involved in a whole spate of activities from golf to bowling.

If you visit Ken and Pat, perhaps you will be fortunate enough to be invited down to Ken’s workshop. To reach it you will pass through a rec room that is decorated in an unusual way. Warplanes still fly in the framed photographs. There is a beautiful frame that Ken made to hold medals, the medals he was given for surrendering his life to the roulette of war. There is a large model of a Lancaster bomber, painted to exactly duplicate the plane that brought Ken back from death time and time again.

Ken does not dwell of his memories of the Second World War; or, if he does, he’s done a marvelous job of hiding it. I only heard Ken talk at length about the war once. We were at the big Commonwealth Air Training Plan reunion in Winnipeg. Douglas Bader and Adolf Galland were there, and so were Ken, his brother and cousin. There was no talk of the horrors of war. I stood there like a puppy, listening while they reminisced about being on leave in bomb-ruined London. About the time Ken bailed out, lost his flight boots and landed in a cow pie. They talked about funny times, and about the people that they remembered.

For them, I think, there was no reason to talk of things so horrible that no person should ever be witness to them. Their memories of gunfire, of anti-aircraft and torn-apart warplanes, have become fond memories of the boys who didn’t come home.

I did not know any of the boys who didn’t come home. They were gone, some of them, 20 years before my birth. I did, however, know many of those who came home. Ken came home. That is what I remember on Remembrance Day. Not the fallen, but those who lived in the place of fallen friends. It makes a war that raged years before my birth a personal and terrible thing.

People like Ken, people of my father’s generation, showed me from the very beginning how to value my home and country. If I ever face my own September, 1939, I will still remember.